I have been serving the Wikimedia community as a volunteer since 2005 in almost every possible role, and have devoted a large part of my professional career to advancing the Wikimedia mission. I do this out of a deep commitment to free knowledge for all, and a belief that knowledge makes the world a better place.

I have made many like-minded friends along the way. What started with a single edit on Wikipedia eventually led me to places I didn’t expect, like publishing books, appearing on national television, immigrating to the United States, creating software, photographing heads of state & Hollywood celebrities, and learning more about copyright laws than any human being ever should.

The Stakes of Knowledge

Fred Kearney on Unsplash.

Knowledge has real consequences on human lives, both for individuals and for societies. As I reckoned with the privilege of growing up surrounded by books, I deepened my understanding of knowledge and the real power it holds, both as an instrument of liberation, and as a vital component of our collective survival.

Recent work

Photoholgic on Unsplash.

My most recent work at the Wikimedia Foundation focused on long-term thinking, strategy, and executive initiatives. I also played unofficial roles as a Wikimedia historian, mentor, and “ship’s counselor.” In my last position, I served as Chief of Staff to the Chief Product and Technology Officer.

Revenue strategy and long-term thinking

I previously led special projects for the Wikimedia Foundation’s Chief Advancement Officer, serving as the department’s de facto chief of staff. In this role, I was leading the organization’s future thinking towards resilience in a changing world, navigating unknowns in technology, policy, industry, society, and climate, notably through scenario planning.

I led Revenue Strategy research and the development of new revenue models for financial growth and long-term sustainability. I also provided expertise and guidance to other teams in the Advancement department, like the Major Gifts team.

Wikimedia 2030

In 2016–2017, I was a Lead Architect for Wikimedia 2030, a global, participatory strategy process involving dozens of movement organizations and thousands of individuals. I was key in designing the process and guiding the movement through an intense exercise involving several cycles of community discussions, in-person events, interviews with experts, and commissioned research.

I led the synthesis of all inputs, conversations, and research into several drafts that were further discussed and edited. I was the main author of the Strategic Direction that emerged and went on to be endorsed by nearly a hundred Wikimedia organizations around the world.

The Strategic Direction of “Knowledge Equity and Knowledge as a Service” now serves as the compass for multi-year strategic planning by Wikimedia organizations, and guides decision-making around roles, responsibilities, and resources in the Wikimedia movement.

Culture & identity

Being a Wikipedian isn’t just about being a modern Diderot, however noble that is. The process through which that sum of knowledge is developed is what makes it so valuable; that’s why, over the years, I have studied the history of Wikipedia, and sought to better understand its culture and identity.

A culture of sensemaking

I recognized myself early on in the Wikipedia vision of collecting and sharing “the sum of all knowledge.” Wikipedians document the world, relying on facts and verifiable information, working in harmony (as much as possible) with complete strangers in pursuit of the best encyclopedic content possible. They integrate sources and organize content, working across language communities and collaborating with other Wikipedians around the world.

Wikipedians have a unique affinity and talent for collecting and curating free, reliable knowledge. In a world of information overload, bias, and misinformation, they provide discernment, sensemaking, and human judgment on information, which all contributes to building trust.

This is something I started to ponder back in 2010 (fr) when I mused about how Wikipedians’ habit of adding reliable sources to Wikipedia articles was seeping into many other areas of their lives, something I had experienced myself when I was writing my Ph.D. thesis: the jury said they had never read such a well-referenced and well-structured thesis. This realization finally crystallized much later as I was reflecting on the Wikimedia Foundation’s revenue strategy and identifying sustainable differentiators of Wikipedia.

Humor is also part of the Wikipedia culture. This collage was my take on the “What people think I do / What I really do” meme, which “depict[s] a range of preconceptions associated with a particular field of occupation or expertise” and “compares varying impressions about one’s profession held by others, self-image and the often mundane reality of the job.” (from Know Your Meme). Images by John Blyberg, Mr Thinktank, PierreSelim, Garry Knight, and Louis-Michel van Loo, on Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0.

Wikipedians organize, weigh, and contextualize facts; as a collective, they constitute a formidable sensemaking engine. Wikipedia, as a website, is merely the current manifestation and artifact of that ethos.

Working as a community

Barn raising is a fundamental concept in the study of online communities. Barn raising “occurs when a community actively decides to come to the same place at the same time to help achieve some specific goal.”[1] The metaphor comes from the collective effort needed to raise an actual barn,[2] a process that is all but impossible to do on one’s own, and demands collaboration and good will from the community.

While mostly reminiscent of 18th- and 19th-century rural North America, barn raising is only one example of communal work encountered in many societies around the world.[3] The Indonesian concept of Gotong royong similarly refers to carrying burdens together, which sometimes translates to literally carrying your neighbor’s home to a new location.[4]

“The spirit of mutual cooperation in moving the house of one of the residents is shown by the fishing community of Binuangeun Malimping Beach, West Java.” // Herusutimbul on Wikimedia Commons // CC-BY-SA 4.0

Wikis are built by people coming together to achieve something that one person couldn’t do alone. Most human endeavors are no different; it takes a collective effort to carry our burdens together, and build in the wiki spirit of good-faith collaboration. Only then can we raise the barn as a community.

Stating our Values

I had another opportunity to understand what brings Wikipedians together in 2016, when I co-led an extensive conversation to discuss and identify the Wikimedia Foundation’s values. I developed a framing for the discussions, based on academic research, industry practices, and the history of the Wikimedia Foundation. This framing invited the different stakeholders (staff, Board, volunteers) to think deeply about what motivated them to be part of the movement, and helped identify the organization’s values as “the core intrinsic beliefs that drive us towards our vision.”

This project was also an opportunity for me to better understand my own motivations and values. As we were writing the final set of values, I realized how closely my own beliefs resonated with them, and why I felt so much at home at Wikimedia.

My colleagues in the Foundation’s Talent & Culture team have been leading the efforts to bring those values to life and integrate them into the employee life cycle, from hiring to onboarding and performance evaluation. In 2018, we organized a workshop to invite employees to express how they approached the values in their work. They did so through a variety of media ranging from poetry to mixed media, dance, clay, or just plain discussion.

In 2022, I was part of an effort to refresh those values through a small-group discussions among Foundation staff, initially focusing on “We are in this together.” This work continued into 2023, extending to the other values.

History & Wikiarchaeology

As someone who has been part of the Wikimedia movement for a long time, I consider it my responsibility to help preserve its collective history and institutional memory. Remembering history isn’t just a crucial part of staying true to who we are; it’s is also how we understand how the past has shaped our present.

Document all the things

Keeping a history of nearly everything is central to the Wikipedia culture. Some of this custom originates in the wiki platform itself: when anyone can edit the site and change its content immediately for all subsequent visitors of a page, it is necessary to keep a diligent history, if only to be able to undo malicious or misguided changes.

My adaptation of the “X all the things” meme, based on the original artwork by Hyperbole and a Half (all rights reserved).

The obsession of Wikipedians with documentation and record-keeping is both a blessing and a curse when it comes to studying the history of the Wikimedia movement. A blessing because hardly anything ever disappears completely from the archives of the site. A curse because the overabundance of historical artifacts and documents makes wikiarchaeology a relentless exercise in endurance, perseverance, and often luck.

Who documents the documenters?

My commitment to understanding and preserving Wikipedia’s collective history has manifested in several ways over the years. For example, in 2013, I produced an interactive timeline to serve as a retrospective of what had happened across the Wikimedia movement that year. In 2018, I led a workshop for the Wikimedia Foundation’s Advancement team to spark the transmission of knowledge. Old-timers shared stories and memories that they thought newcomers would find of interest, and newcomers asked old-timers questions from a fresh perspective.

The interactive timeline I created in 2013 served as a retrospective of what had happened across the Wikimedia movement that year.

In 2012, I gave a talk at Wikimania, the annual Wikipedia conference, called “Eleven years of Wikipedia, or the Wikimedia history crash course you can edit.” The presentation consisted of a large chronological infographic through which I walked the audience. I also printed the graphic on a large poster and invited the participants to correct or expand its content throughout the conference, in true Wikipedia fashion.

I researched and designed this infographic for my talk “Eleven years of Wikipedia, or the Wikimedia history crash course you can edit.” At the Wikimania 2012 conference in Washington, D.C., I walked the audience through this visual history of the Wikimedia movement; the recording of the presentation is available on YouTube.

Watching the history of the World be written in real time by volunteers is fascinating, especially because you would expect it to fail: in the famous words of Wikipedian Gareth Owen, “The problem with Wikipedia is that it only works in practice. In theory, it’s a total disaster.”[5] Being a witness to this process (and the mini-disasters it goes through along the way) is a captivating exercise in historiography.

Gareth Owen (2006-01-20). “User:Gareth Owen.” Wikipedia.

Product & Technology

I dedicated my first few years at the Wikimedia Foundation to improving the technical platform that makes Wikipedia possible. These successive roles gave me the opportunity to bring together my skills as an engineer, writer, and researcher, and to fulfill my need for interdisciplinary work that spans fields and social groups.

Special projects

Prior to leading the Wikimedia 2030 strategy effort, I managed special projects for the Wikimedia Foundation’s Deputy Director, and served as a strategic advisor to the organization and its leadership team. My job was to step in when needed to lead time-sensitive initiatives and research critical to the Foundation’s product development efforts.

In practice, this meant leading initiatives like the File metadata cleanup drive. The high number of files missing machine-readable copyright information was blocking the wide release of MediaViewer, the plugin that opens images in full screen on Wikipedia pages. The plugin needed to be able to read the copyright information from the images to comply with license requirements. I created an automated dashboard to measure and identify the files with unreadable data, and organized community efforts to fix them. In three months, the cleanup drive had contributed to eliminating a third of the unreadable files across all wikis, fixing over 800,000 files.

I coded an online tool in Python to query tens of millions of multimedia files across all Wikimedia sites, and check that their copyright information was easily accessible by automated programs.

In this role, I also produced a research report on the roles performed by Wikipedia contributors, based on a literature review of over a hundred scientific publications. The report helped product managers and designers understand scholarly knowledge about Wikipedia and online communities in a language that spoke to them. In addition, I supported the VisualEditor team with quality assurance research to identify critical software bugs, and analyzed the most cited websites in Wikipedia references to improve automated citation formatting. Those efforts enabled the team to move forward with a wider release of the visual editor to Wikipedia contributors.

“Guillaume understands many of Wikimedia’s workflows deeply. … he loves documenting, analyzing, breaking apart things and putting them back together in novel ways. He’s awesome at information architecture, and at really thinking through all the options to solve a complex product problem.”

—Erik Möller, Deputy Director and VP of Product & Strategy (2014).

Multimedia usability project

I first joined the Wikimedia Foundation’s staff in October 2009 as a Product Manager for Multimedia Usability. As a Product Manager, I sought to understand the needs of Wikipedia contributors and translate them into product requirements that could be implemented by engineers. Because the Foundation was much smaller back then, I also served as UX designer and usability researcher.

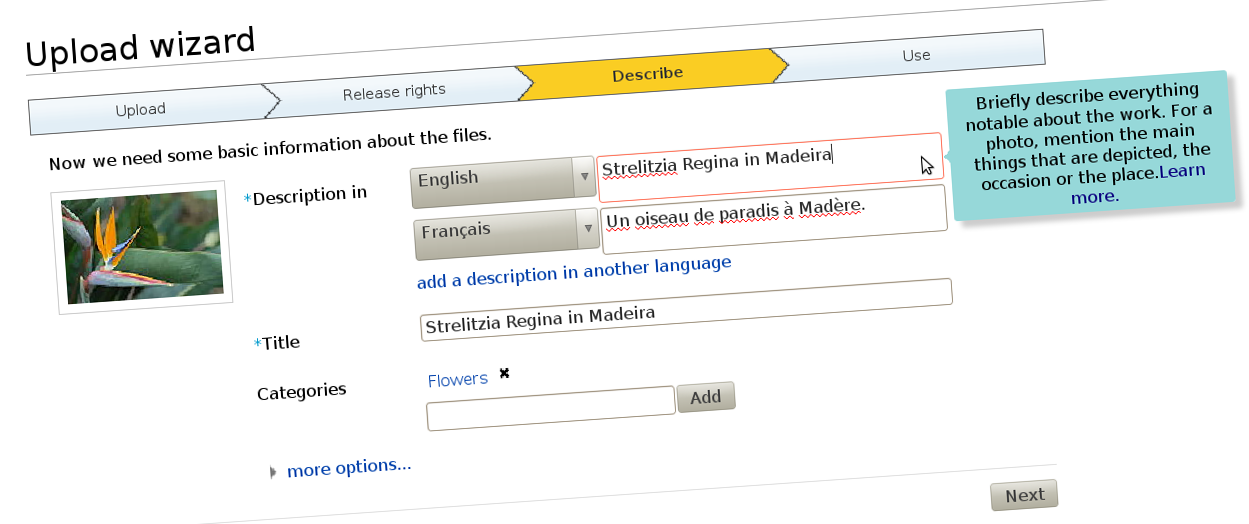

The Multimedia Usability Project was a special project to increase multimedia participation on Wikimedia sites, through an overhaul of the uploading process to Wikimedia Commons, the central media repository for all language editions of Wikipedia. The two-person team was funded by a grant from the Ford Foundation.

As a Product Manager, I led the development of UploadWizard, a multi-file upload system designed to make it easier for contributors to upload pictures to Wikipedia. It has now been used to upload over 38 million files.

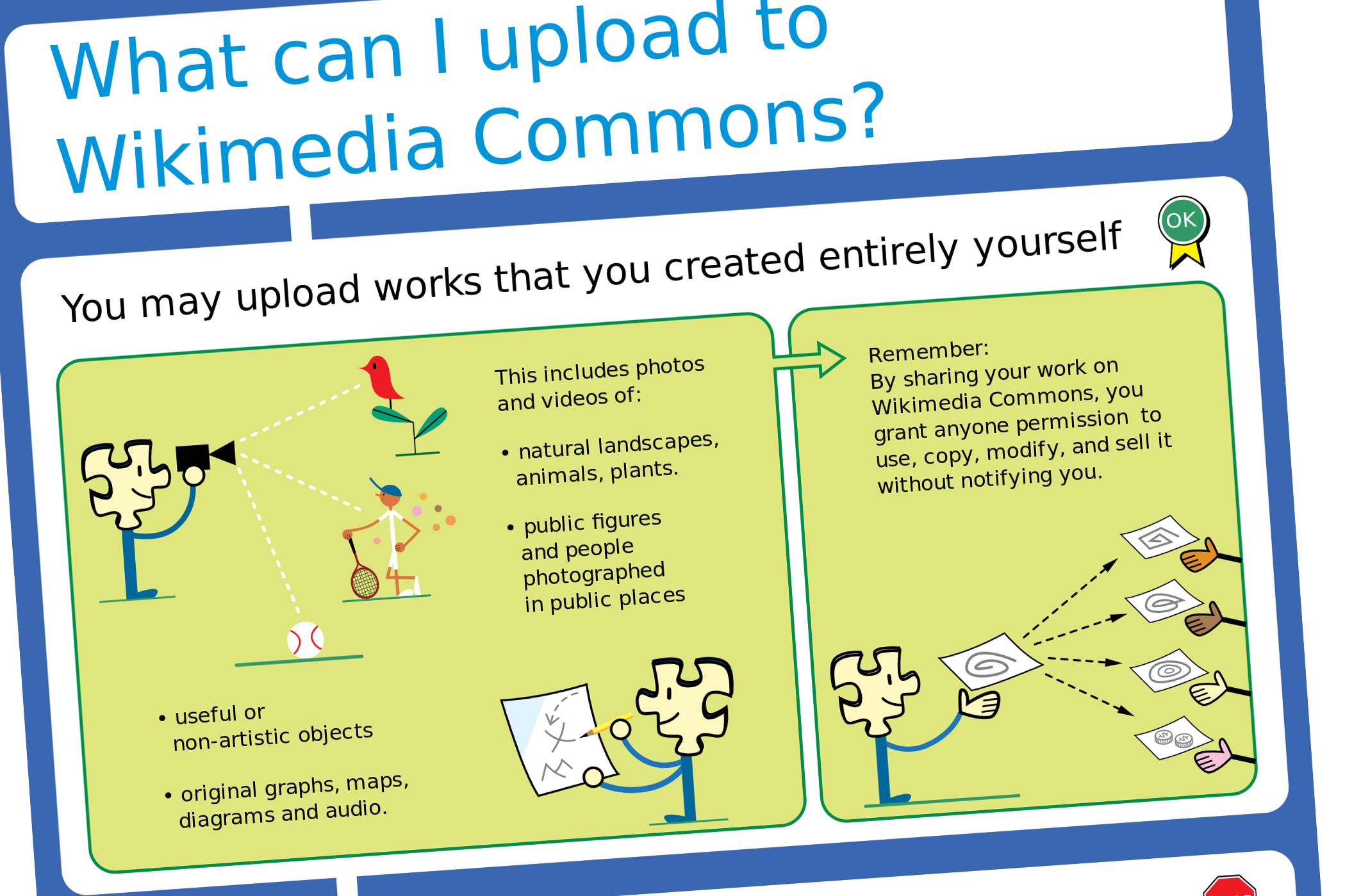

Two main products were delivered as part of the project, both based on extensive user research: a new multi-file upload system for Wikimedia Commons, featuring a wizard-style interface; and an illustrated licensing tutorial, explaining the basics of copyright and free licenses in plain language. More features were added after the completion of the grant, notably to support campaigns and contests like Wiki Loves Monuments, a worldwide contest that was recognized by the Guinness Book of Records as the largest photography competition.

I worked with a graphic artist to develop an illustrated tutorial explaining the basics of copyright law and free licensing to new contributors.

As of March 2025, 1.8 million unique users have used UploadWizard to upload over 38 million files to Wikimedia Commons.

Technical writing

Transparency is a guiding principle of the Wikimedia Foundation: it ensures that the organization is accountable about its activities to the general public and its donors, and that Wikipedia contributors have a say in changes that affect them on the site.

As a technical writer, I translated techspeak into communications for multiple audiences on a wide spectrum of specialized technical expertise. I was responsible for assembling, editing, and publishing the monthly engineering reports covering technical activities for the whole organization. I was also the editor of the Wikimedia Tech Blog, writing and editing technical blog posts on a variety of topics from software updates to data center migrations.

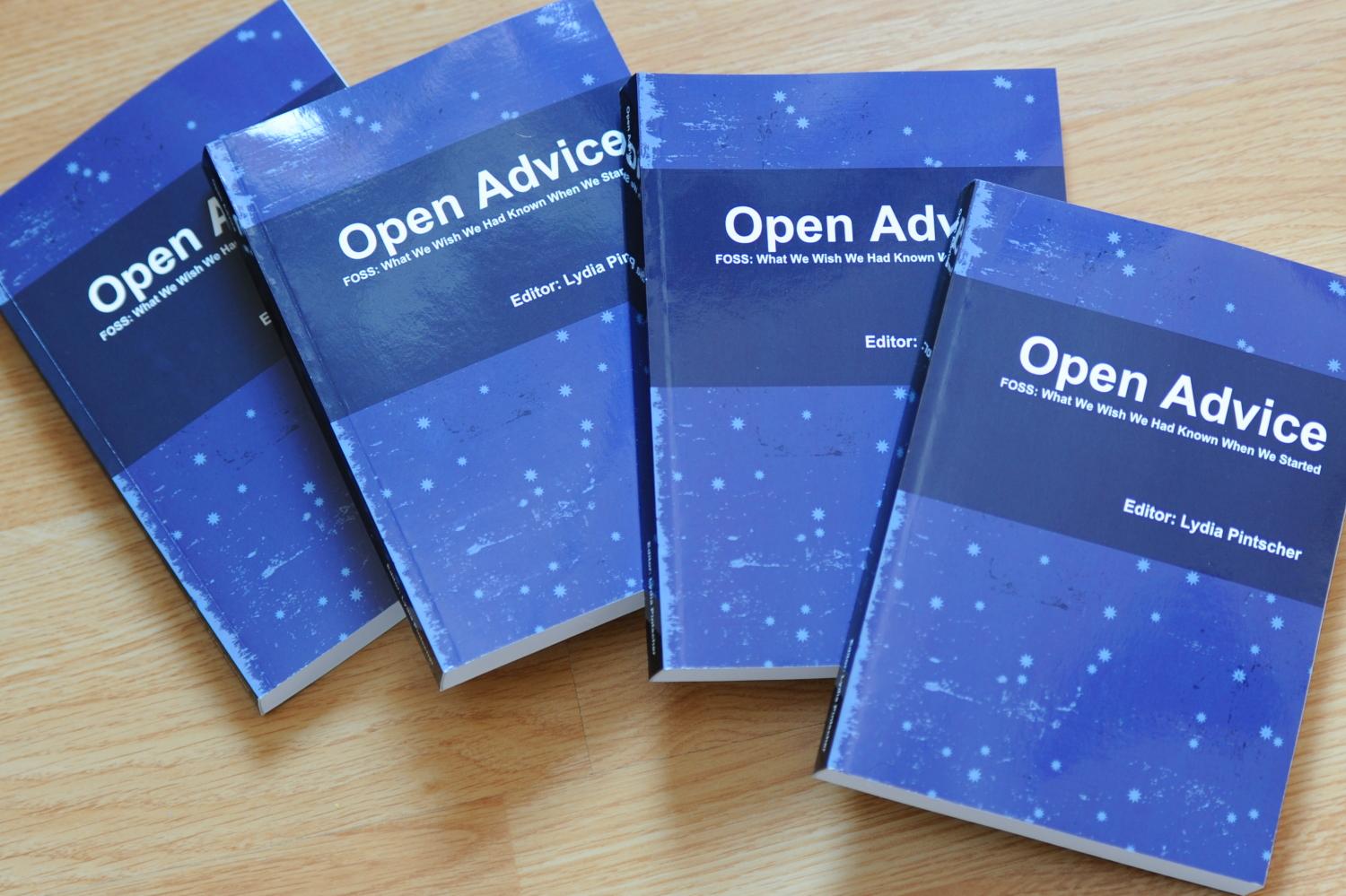

During that period, I authored a few book chapters. One detailed the architecture of MediaWiki, the software that powers Wikipedia, for inclusion in The Architecture of Open Source Applications, volume 2. Another one, on the topic of user experience, was included in Open Advice, a collection of essays, stories and lessons learned by members of the Free Software community.

I contributed a chapter on User Experience to the Open Advice book, a collection of essays, stories and lessons learned by members of the Free Software community.

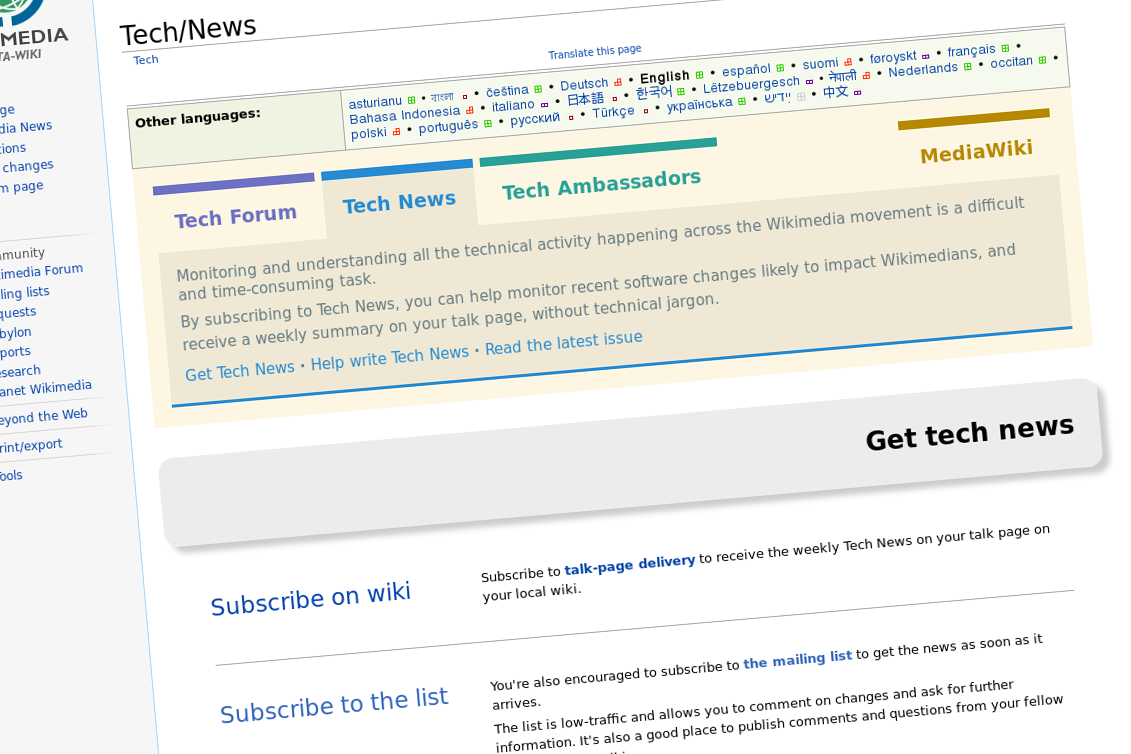

In 2013, I started Tech News, a weekly technical newsletter for Wikipedia contributors. Written in intentionally simple language, its goal was to inform Wikipedians without specialized technical knowledge about software changes that might affect them. I worked with volunteers to translate the newsletter in about a dozen languages every week, and wrote a Lua script to distribute multilingual newsletters. The newsletter, now managed by the Community Liaisons team, has been running for seven years and has been instrumental in improving relationships between engineering staff and Wikipedia communities.

Tech News, a weekly technical newsletter I created in 2013 for Wikipedia contributors, has now been running for seven years and has been instrumental in improving relationships between engineering staff and Wikipedia communities.

Community organizing

Wikimedia affiliates are local and thematic organizations that organize events and run programs to support Wikipedia and its sister sites. I got involved with Wikimedia France in 2006, and later organized one of the first annual meetings of Wikimedia affiliates in Berlin.

Wikimédia France

In 2006, I gave my first presentation about Wikipedia, the first of many. I started becoming more involved in public outreach, workshops, and training. I also started volunteering for Wikimédia France, the local Wikimedia chapter, and a few months later I was elected to its Board. The chapter was small and had no paid staff, so Board members took on the work and responsibilities that would traditionally be in the purview of staff.

Holding the Commons with Brianna and Cary at Wikimania 2007 in Taipei, Taiwan. (From Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0.)

As a Board member, and later also Secretary, I focused on transparency, efficiency, and community organizing at the local level: I managed membership logistics, engaged donors, and streamlined the Board’s decision making process. In addition to a Board member’s usual responsibilities around governance, I also created an internal newsletter to keep members informed, and organized the chapter’s activities into working groups to facilitate the involvement of volunteers.

Wikimedia Chapters conference 2009

In 2009, I moved on to Community organizing at the global level, and organized one of the first annual meetings of national Wikimedia chapters, on behalf of Wikimedia Deutschland. Representatives from 23 countries and the Wikimedia Foundation attended the conference in Berlin. I developed the conference’s program in advance with the participants, balancing competing interests and navigating movement politics. I also coordinated travel arrangements and subsidies between chapters, to ensure that all the groups were represented at the meeting.

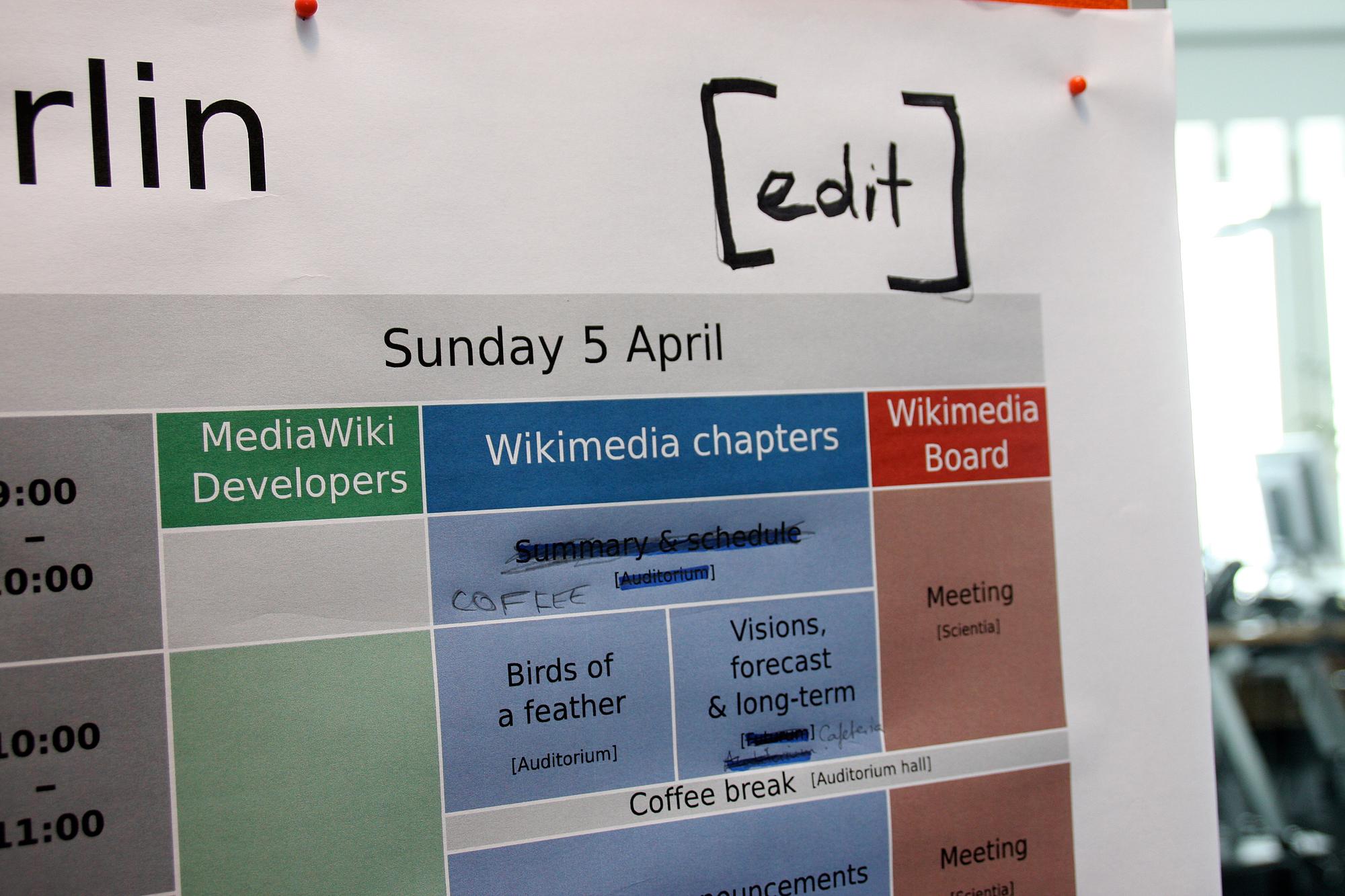

Photograph of the conference’s schedule. (Elke Wetzig on Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0.)

The conference was a success, and went on to be replicated every year since. Now called the Wikimedia Summit, it has become one of the main venues for the Wikimedia movement to discuss governance, determine strategy, and share experiences.

External communications

The Wikimedia movement has always relied heavily on the work on volunteers, and even more so in its early years. When the Foundation was a lot smaller, I supported its Communications staff, answered press requests, and co-led the team of volunteers who respond to emails sent to Wikipedia by the general public.

Press & Communications

Among the many areas in which I volunteered for the Wikimedia movement over the years, I was particularly involved in Communications, back when a single employee staffed that function at the Wikimedia Foundation.

“Guillaume wasn’t really a ‘volunteer’ … he was a very important part of the communications department. … He is a pleasure to work with - super professional and upbeat; He is incredibly bright - his instincts and creativity are beyond superb; And most importantly, he was a source of great support that allowed the foundation to grow to what it is today. Truly a blessing to have worked with him.”

—Sandra Ordonez, Communications Director (2008).

I created and designed corporate documents and graphics, such as press kits and fundraising prospectuses, and provided visual identity advice. I also answered press requests from international news outlets about Wikipedia and its sister sites, at a time when Wikipedia was not as well-respected and understood as it is today.

Volunteer response team (VRT)

In 2007, I joined the Volunteer Response Team who answers the emails sent to Wikipedia by the general public. This group of 300+ trusted volunteers also used to be referred to as “OTRS agents,” after the name of the customer service software we used.

Responding to emails sent to Wikipedia sometimes feel like a sisyphean endeavor: VRT volunteers respond to thousands of emails every year, while ensuring the confidentiality of the messages and protecting the privacy of the people who email us. Many emails are similar and can be answered using canned responses. However, those in the Pareto minority are often related to complex questions or tricky conflicts, and require much more time; they involve research, lengthy back-and-forth, and sometimes mediation.

Responding to emails sent to Wikipedia is often about reminding people that anyone, including themselves, may edit the articles to correct the mistakes they encounter (unless they have a conflict of interest), which led me to make this parody of the “Keep Calm and Carry On” poster. (from Wikimedia Commons // Original poster in the public domain; hand icon by Mushii // CC-BY-SA 3.0)

After a few months, I became a team leader (“VRT administrator”), which gave me access to advanced tools to manage queues, volunteers, and canned responses. In that capacity, I vetted, recruited, and onboarded dozens of new volunteers to respond to email in many languages. I also improved processes so that agents could focus their time on responding to emails.

Editing Wikipedia

The Gnome Artist. Oil painting on canvas by Heinrich Schlitt // Public domain.

Since 2005, I have been editing Wikipedia in several languages, from making small grammar fixes, to writing whole articles, to facilitating community processes behind the scenes.

It starts with a single edit

I made my first edit to the French-language Wikipedia in August 2005 to fix a spelling mistake. My second edit was to fix a conjugation mistake. My third edit was to fix spelling and punctuation mistakes. I guess you could say there was a pattern.[6]

First and second edit to Sable bitumineux, third edit to Calculateur stochastique, all on August 18, 2005. These are all typical examples of the work of a wikignome, i.e. “a wiki user who makes useful incremental edits without clamoring for attention. WikiGnomes work behind the scenes of a wiki, tying up little loose ends and making things run more smoothly.”

Most of my early edits were to articles related to my studies and my work, like adding content to the article about nanotechnology, adding a schematic to the one about atomic force microscopy, or translating the English-language article about the electrical double layer to French.

I quickly moved on to reverting damaging edits made by vandals, contributing to the Oracle (a convivial reference desk on Wikipedia), welcoming new users, and participating in community discussions (using an obnoxiously colorful signature). I became an “administrator” on Wikipedia and a few other sites, like Wikimedia Commons and Meta-Wiki. I also started operaring a “bot,” i.e. an automated program to make repetitive edits: the Seven-League Bot (and its French alter ego, the Bot de Sept Lieues).

The avatar of the Seven-League Bot was Gustave Doré’s 19th century engraving of Le chat botté (Puss in Boots). Wikimedia Commons // Public domain.

Since then, I have made over 50,000 edits across hundreds of Wikimedia wikis, and I have spent most of my professional career supporting the Wikimedia movement in various roles. I still occasionally make the odd edit when I come across something I can fix on a Wikipedia page.

Crosswiki service work

For a few years, I served as a member of the Wikimedia “Stewards,” a handful of individuals entrusted with wide-ranging powers across the different language versions of Wikipedia and its sister sites.

Stewards have the sensitive ability to grant and remove rights on any of the hundreds of thousands of user accounts across wikis, as well as complete access to the software interface on all wikis. Use of those powers is regulated through policy. Although most of a steward’s work is routine, they occasionally intervene in case of emergencies, like rampant vandalism or a rogue administrator abusing their tools.

Serving as a steward and as part of the Small Wiki Monitoring Team gave me an opportunity to work with contributors from a variety of languages and backgrounds over the years. I was left with a deep appreciation for their work, particularly in communities with few native speakers.

Photography and Wikimedia Commons

by Steven Walling on flickr // CC-BY-SA 2.0.

Shortly after I started editing Wikipedia, I became a contributor to Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. What started as a side project eventually led me to photograph heads of state and Hollywood celebrities, and my work to be published in books, journals, and major magazines.

Wikimedia Commons, like Wikipedia, only accepts cultural works released under a free license or in the public domain.[7] Therefore, many subjects remain devoid of illustration because Wikipedians can’t use promotional materials created by others. This gap is particularly visible on biographies of politicians, people from the entertainment industry, and other public figures.

Free cultural works, or works released under a free license, “can be freely studied, applied, copied and/or modified, by anyone, for any purpose” including commercial use. See the definition on Freedom defined.

(Technically, some language editions of Wikipedia accept non-free content, such as cover art and movie posters, under very specific conditions, but those are exceptions we don’t need to get into right now. In the words of Sue Gardner, former Executive Director of the Wikimedia Foundation, who was addressing Wikimedians in Buenos Aires in 2009: “You all know more about copyright law than any sane, sensible human being.”)

In 2007, I started to attend events specifically to take pictures of hard-to-photograph subjects. I covered political rallies to take pictures of politicians running in the 2007 presidential election, photographing 8 out of 12 candidates, including the two finalists. The same year, I was the photographer for the 11th International Conference on Miniaturized Systems for Chemistry and Life Sciences (µTAS 2007), where I was also presenting my research.

Later, I attended comics and film conventions like WonderCon and the Alternative Press Expo in San Francisco and Anaheim, CA. In 2014, I was accredited to attend the 37 G8 summit in Deauville, France, where I photographed heads of government such as David Cameron (Prime Minister of the United Kingdom) and Naoto Kan (Prime Minister of Japan).

Beyond Wikipedia, my pictures have now been published in many other venues, from specialized technical publications (like a university-level physics textbook[8] and an academic journal about psychology[9]) to magazines like Science,[10] The Smithsonian,[11] and ELLE.[12]

Bauer, Wolfgang and Westfall, Gary D. (2010). “Chapter 11: Static Equilibrium.” University Physics with Modern Physics. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 354. ISBN 978-0-07-285736-8. OCLC 436028189. “Figure: 11.1: The tallest building in the world as of 2008, Taipei 101 in Taiwan: … (b) view of the sway damper inside the tower.”

Joye, Yannick (2007-12). “Architectural Lessons from Environmental Psychology: The Case of Biophilic Architecture.” Review of General Psychology. 11 (4): 305–328. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.11.4.305. ISSN 1089-2680. Full-text PDF. “The interior of Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia contains schematic interpretations of natural contents. Left: columns as treelike structures. Right: flowerlike canopies.”

Sumner, Thomas (2014-02-16) “How to Hide Your Genome.” science.org. doi:10.1126/article.23537. “Genetic gold. Each spot in a DNA microarray, such as this one, contains large amounts of sensitive genetic information.”

Binkovitz, Leah. “PHOTOS: Orchids of Latin America.” Smithsonian Magazine. 2013-01-25. “Paphiopedilium appletonianum.”

“ELLE СТИЛЬ ЖИЗНИ.” ELLE Russia. 2015-04. p. 325. ISSN 1560-3180. “Пляжные кабинки с именами звезд, которые ими пользовались, — одна из изюминок Довиля.” (“Beach cabanas with the names of the stars who used them are one of the highlights of Deauville.”)