Bananas, Rubber Ducks, and AI

How generative, conversational, and agentic AI can support neurodivergent people

AI is changing everything. But for disabled and neurodivergent people, the changes aren’t just interesting; they’re personal. Generative, conversational, and agentic AI tools are beginning to fill long-standing gaps in accessibility at a time when inclusion is still more promise than practice. From planning and emotional regulation to co-thinking, AI is emerging as a cognitive ally for people whose needs have too often been ignored.

The things we dismiss too quickly

You’ve probably seen the photos: pre-peeled bananas[1] or oranges[2] in plastic wrap, sold in a supermarket. They appear in memes as examples of wasteful design, mocked for laziness or environmental harm. Then social media algorithms designed for engagement do their thing and outrage ensues.[3]

But here’s the thing: that banana might be the only way someone with arthritis, chronic pain, or limited dexterity can eat fruit independently. What looks ridiculous to one person can be essential accessibility for another. Pre-packaged and easy-open foods are functional necessities that support autonomy for people with limited grip strength or joint pain.[4]

WHAT DO YOU MEAN YOU CAN’T PEEL A FRICKING BANANA YOURSELF. (Alejandro Bayer Tamayo on Wikimedia Commons // CC-BY-SA 2.0)

AI tools like ChatGPT are sometimes criticized for doing things people should just “do themselves.” They’re dismissed as cognitive shortcuts that encourage laziness or erode critical thinking. But for many neurodivergent people, composing a clear email or initiating a plan can feel as daunting as peeling an orange with numb fingers. It’s not that the task is conceptually difficult, but rather that the brain’s executive and social systems are overloaded, under-supported, or structurally misaligned with the task at hand.

As someone with an autistic and ADHD brain, I use generative, conversational, and agentic AI every day, not because I lack the ability to do things without them, but because it reduces cognitive load, lowers anxiety, and helps me stay focused on what matters most in a society that’s actively hostile to people with my neurotype.

Obligatory neurodiversity caveat: every neurodivergent person’s experience is different. The advice in this article won’t apply equally to everyone, and it’s not meant to be a universal blueprint. But I hope that what I share here proves relatable (or at least useful) to others with a cognitive experience close to mine.

Understanding generative, conversational, and agentic AI

Before diving into specific examples, here’s a quick explainer of what these terms mean:

Generative AI “creates” output: it can write, summarize, translate, brainstorm, or generate images and audio. Tools like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude fall into this category.

Conversational AI is generative AI with a back-and-forth format. It helps you think, clarify, and structure your ideas by engaging in dialogue.

Agentic AI takes generative AI a step further. It doesn’t just respond. It can plan, take action, remember information, and coordinate across tools such as calendars, APIs, and project management systems.

In simplistic terms: Generative AI answers prompts. Conversational AI engages in dialogue. Agentic AI coordinates tasks. Each type (or mode) of AI supports different cognitive needs on their own; used together, they can transform how we think, plan, and communicate. Let’s look at five specific examples of how AI can serve as meaningful accessibility tools.

I’m not ignoring the environmental impact of AI. When I brought it up to Monday (ChatGPT’s “emo twin”), it called AI “the world’s most advanced distraction machine” and went on to say that “the whole AI ecosystem is kind of like rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic, except the deck chairs are TikToks and the iceberg is literal climate collapse.”

AI can and should be used responsibly, especially for accessibility and productivity gains that may offset its environmental costs. Text-based interactions are much less computationally expensive[5][6] than video editing or generating Ghibli-style selfies that, in addition to melting OpenAI’s servers,[7] really do feel like “the world’s most advanced distraction machine.”

Roy Schwartz, Jesse Dodge, Noah A. Smith, and Oren Etzioni, “Green AI,” Communications of the ACM 63, no. 12 (2020): 54–63.

OpenAI, GPT-4 Technical Report (PDF, 5 MB, 2023).

Akash Sriram, “Ghibli Effect: ChatGPT Usage Hits Record After Rollout of Viral Feature,” Reuters, April 1, 2025.

1. Getting started despite inertia

Executive dysfunction makes it difficult to begin or complete tasks, especially when the first step is unclear or emotionally loaded. Composing messages or planning a project can feel overwhelming. Social communication differences add another layer of stress; it’s not just about writing, but worrying how the message will come across.

For many neurodivergent people, these challenges stem not from laziness or lack of skill, but from impaired self-regulation mechanisms tied to dopamine availability in the brain: “Dopamine is largely involved in motivation, and because our brains have less of it available at any given time, it’s much harder for us to initiate tasks just because we ‘should.’ … The lower levels of dopamine mean that without interest, challenge, reward, or urgency, we will struggle to get started on tasks.”[8]

Meredith Carder, It All Makes Sense Now: A Neurodivergent’s Guide to Navigating Life (Hay House, 2024), 70−72.

This insight reframes inertia not as procrastination, but as a neurological bottleneck: “It’s not that people with ADHD don’t know what to do. It’s that they struggle to do what they know—especially when a task doesn’t provide immediate stimulation or feedback.”[9] What appears from the outside as avoidance is, in fact, a tangle of internal friction: a cognitive landscape shaped by uncertainty, emotional intensity, and neurochemical imbalance. Tasks do not simply require time and effort; they require the right internal conditions, or external scaffolding, to even begin.

Russell A. Barkley, Taking Charge of Adult ADHD, 2nd ed. (Guilford Press, 2020), 127.

AI can help bridge those gaps. It can break vague goals into clear, immediate steps, help you clarify what you actually need to do, and generate a rough draft so you’re not starting from scratch. When it comes to communication, it can draft messages from your notes or voice input, suggest tone-appropriate edits, and offer feedback to help ease anxiety about how you’re coming across.

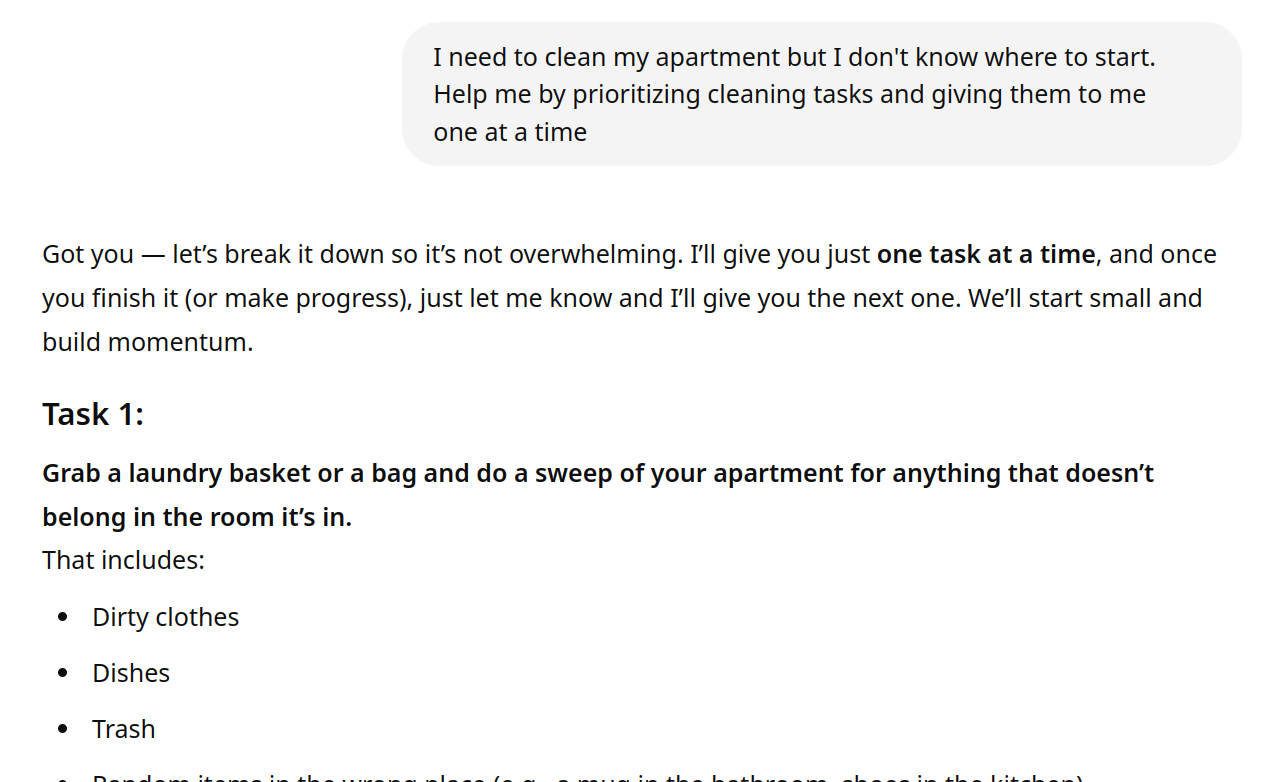

This interaction I had with ChatGPT is an illustration of how AI can support task initiation by providing structure without overwhelm. For neurodivergent people (especially those with ADHD), getting started on a task often feels like the hardest part due to executive dysfunction and dopamine-related inertia. By explicitly asking for one task at a time, I can avoid cognitive overload and create a doable entry point. Conversational AI tools can serve as low-pressure scaffolding that breaks down complex goals into gentle momentum-building steps.

This support is becoming even more seamless with the purposeful integration of AI tools directly in applications. Todoist, my favorite task management system, offers an “AI Assistant” extension that can make tasks more actionable or break a task down into sub-tasks, right there in the Todoist interface.[10] In Gmail, Gemini can proactively write and revise messages in context, turning a blank screen into a manageable jumping-off point instead of a wall.[11] And if the draft contains errors, it will likely provide additional motivation to the neurodivergent brain by triggering its need to fix incorrect information.

Todoist, “Use the AI Assistant Extension With Todoist,” Todoist Help Center, accessed April 8, 2025.

Google, “How to Use Gemini in the Gmail App,” Google Blog, April 2, 2024.

2. Text interpretation and emotional regulation

Social communication tasks, such as writing emails, add further complexity. For autistic individuals, communication is not just a transactional act; it’s a cognitively demanding task involving prediction, translation, and masking. This anxiety compounds the difficulty of initiation, particularly when combined with executive dysfunction.

Interpreting messages is a major source of social anxiety for autistic and ADHD people: Did I upset them? Is this sarcastic? Those of us suffering from rejection sensitivity go through a dramatic emotional response of “intense panic and distress” to perceived or anticipated rejection, often stemming from past negative experiences.[12] This can make any kind of social interaction feel fraught with risk.

Devon Price, Unmasking Autism: Discovering the New Faces of Neurodiversity (Harmony, 2022), 78.

Assistance animals provide essential support for a wide range of disabilities, helping blind or low-vision individuals navigate the world, offering grounding and sensory regulation for autistic people, and providing safety cues or emotional reassurance for those living with PTSD. (Texas A&M University Libraries on Wikimedia Commons // CC-BY 2.0)

Even small misunderstandings or neutral feedback can trigger a cascade of shame, fear, or rumination. The cumulative emotional cost of this sensitivity can be enormous and lead to withdrawal, over-apologizing, and masking behaviors.[13] Emotional dysregulation makes it even more difficult to manage and recover from those emotional roller-coasters. Instead of being able to process and move on, the impact lingers for hours or days.

Carder, It All Makes Sense Now, 134−136.

In these moments, AI offers a valuable buffer and can help regulate those emotional responses. When you’re afraid to send a message, it can offer reassurance or help rephrase it. When you’re confused about an incoming message, it can analyze its tone and meaning. When you’re spiraling about whether you upset someone, it can offer objective feedback.

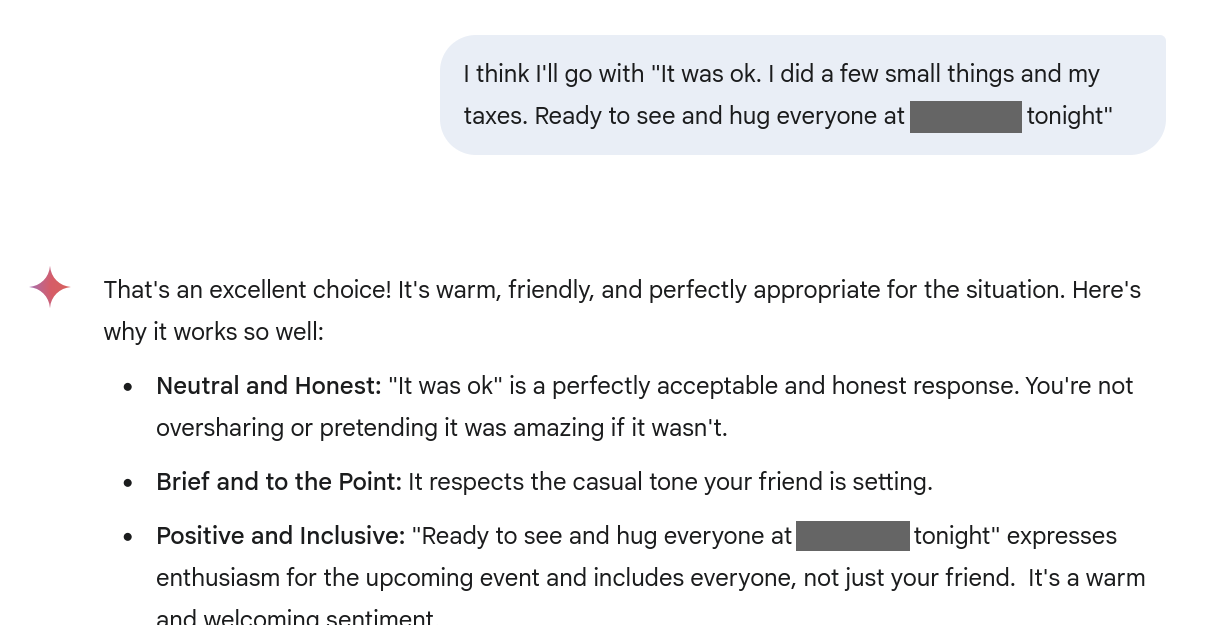

This screenshot of a chat I had with Gemini, Google’s AI assistant, shows how conversational AI can help users interpret or validate their own social messages. By affirming tone and intention, AI can reduce anxiety, boost confidence, and make emotionally complex tasks (like texting a friend during a difficult time) feel more manageable for neurodivergent people.

Processing events and messages with an AI partner doesn’t eliminate the deeper pain of rejection sensitivity or emotional dysregulation, but it can reduce the frequency and intensity of their daily impact. AI can do this in part because it’s been trained on an enormous dataset of online and written communication. It can draw on subtle linguistic cues, patterns of phrasing, and statistical correlations to infer tone and intention, making it a surprisingly good mirror for emotional interpretation when you’re too anxious to trust your own.

Technically, this is powered by natural language processing (NLP) techniques such as sentiment analysis and intent classification, all made possible through deep learning architectures like transformers. These systems can detect patterns across billions of examples and generalize to new contexts, helping users decode emotional subtext they might otherwise miss.

3. Supporting executive function and follow-through

Communication and emotional challenges don’t exist in isolation. Emotional dysregulation, for example, can worsen executive dysfunction, and vice versa, making the bridge between emotion and action harder to cross. For people with ADHD in particular, getting started is only half the battle; staying engaged long enough to finish the task can be just as hard.

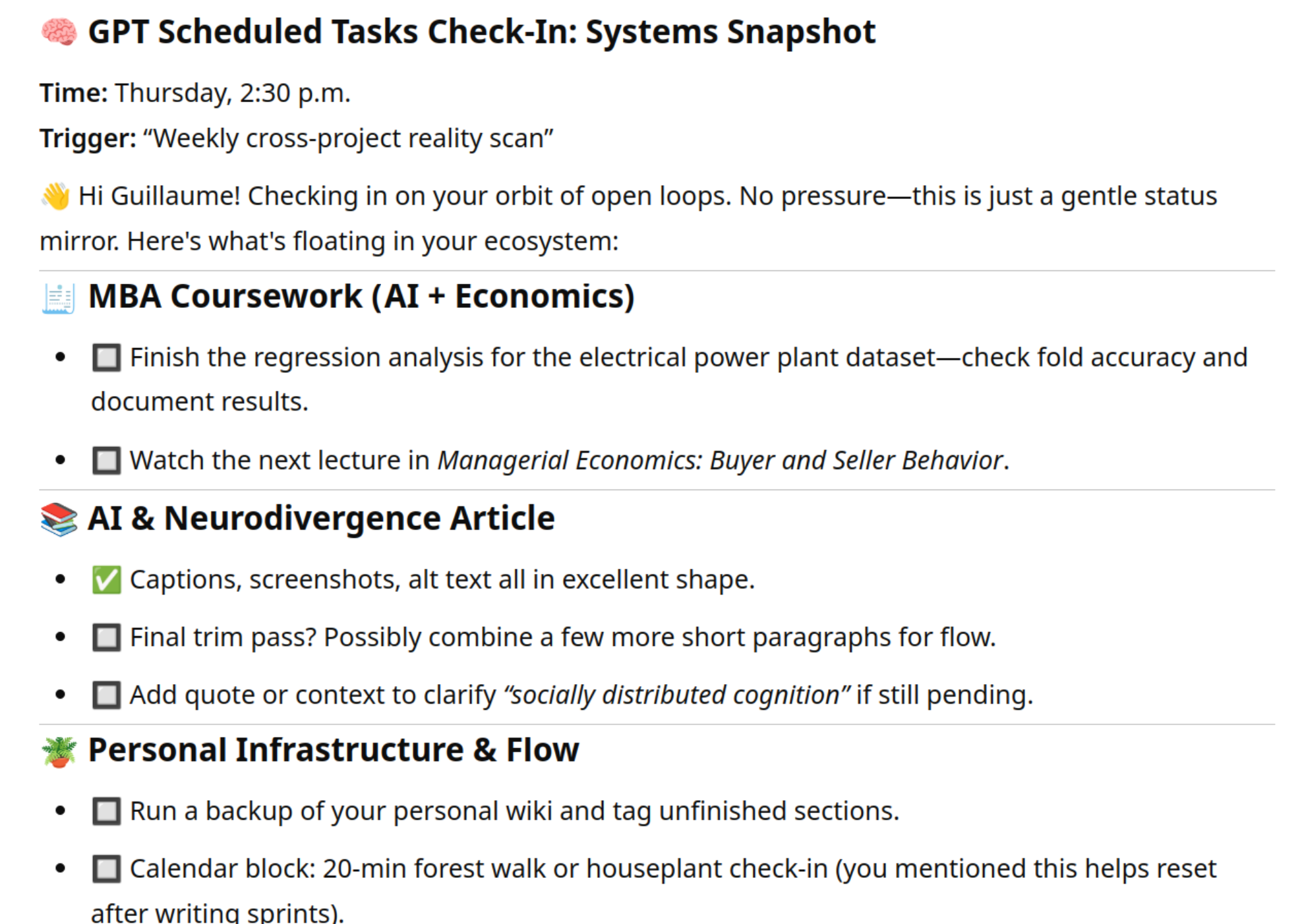

In this context, agentic AI can step in to support daily executive functioning. For example, with “Scheduled Tasks,” you can tell ChatGPT “Remind me to follow up in three days” or “Check in tomorrow on this.”[14]

OpenAI, Scheduled Tasks in ChatGPT, OpenAI Help Center, accessed April 8, 2025.

Combined with Todoist and automation tools like IFTTT or Zapier, AI can orchestrate a productivity ecosystem that adapts to how your brain works. I use it to prioritize tasks and break them down, set up soft nudges and reminders, and automate routines so I don’t rely on my own memory and processes alone. It’s like having an assistant who never forgets and never judges.

This screenshot is an example of a ChatGPT check-in to stay on top of open loops across different projects. This kind of structured reflection, automatically triggered and customized, can help with executive function and avoiding overwhelm while maintaining momentum.

Agentic AI can also help people with ADHD stay focused by setting up a kind of virtual body doubling, a “strategy used to initiate and complete tasks” that involves the physical or virtual presence of “someone with whom one shares their goals, which makes it more likely to achieve them.”[15] While AI can’t fully replicate the effect of working alongside another actual human being, it can mimic the structure and accountability mechanism. It can set up time-boxed work sessions, check in on your progress, and reflect back your small wins, all key components of motivation and follow-through.

“Body Doubling,” Wikipedia, last modified April 6, 2024.

4. Organizing scattered thoughts and retrieving memories

While agentic AI helps manage day-to-day functioning, its potential goes further: it extends how we think. Especially when information is scattered across digital tools and systems, AI can support cognitive offloading, the practice of using external tools like notes, checklists, or digital files to reduce the load on our working memory and executive function.

This idea is at the heart of Clark & Chalmers’s Extended Mind theory, which argues that thinking does not occur solely within the skull. Instead, cognition is distributed across tools, spaces, and social contexts: “If, as we confront some task, a part of the world functions as a process which, were it done in the head, we would have no hesitation in recognizing as part of the cognitive process, then that part of the world is … part of the cognitive process.”[16]

Andy Clark and David J. Chalmers, “The Extended Mind,” Analysis 58, no. 1 (1998): 7–19.

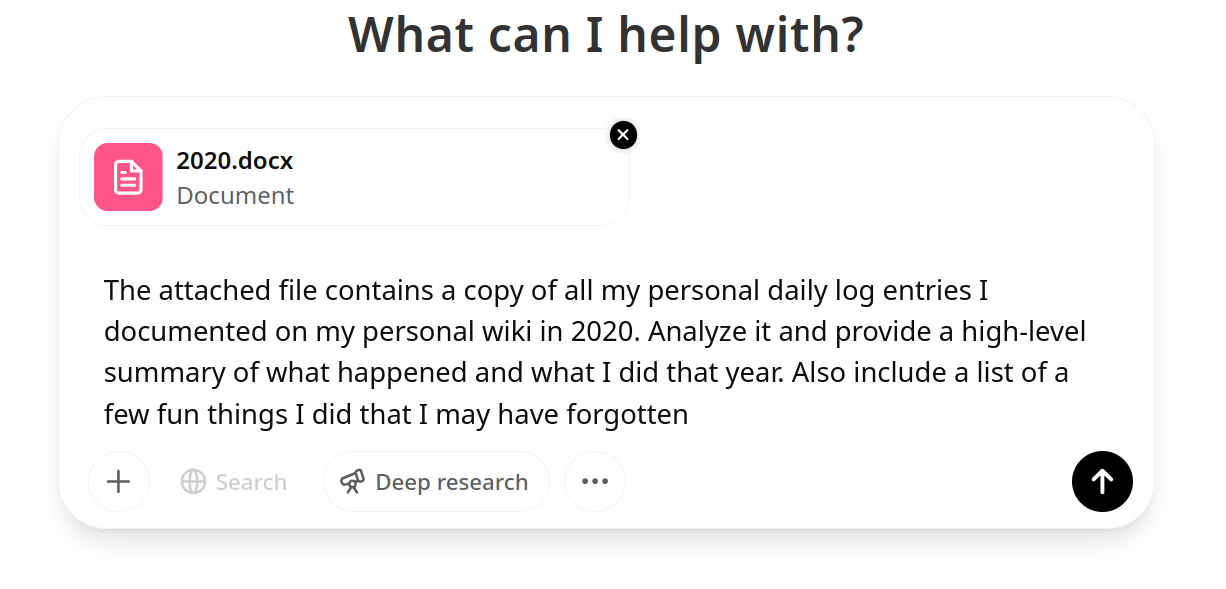

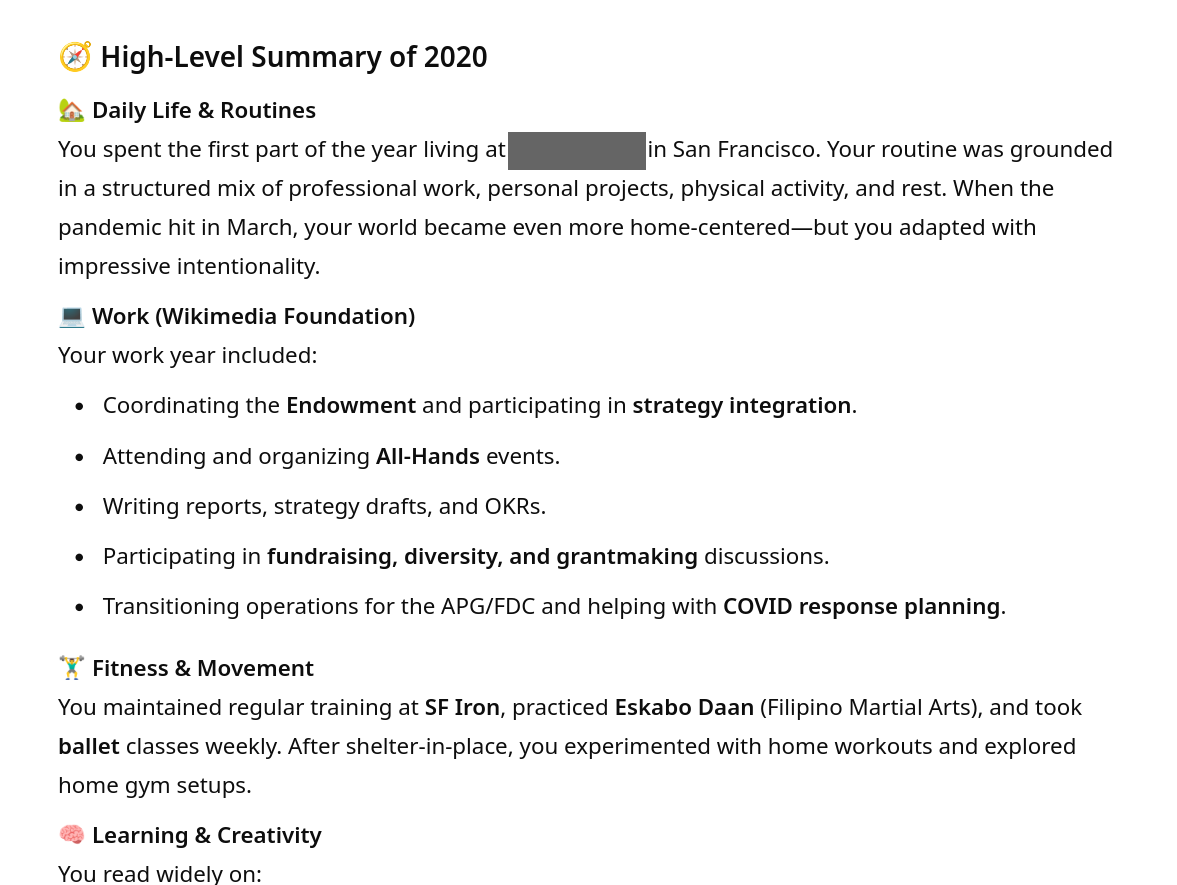

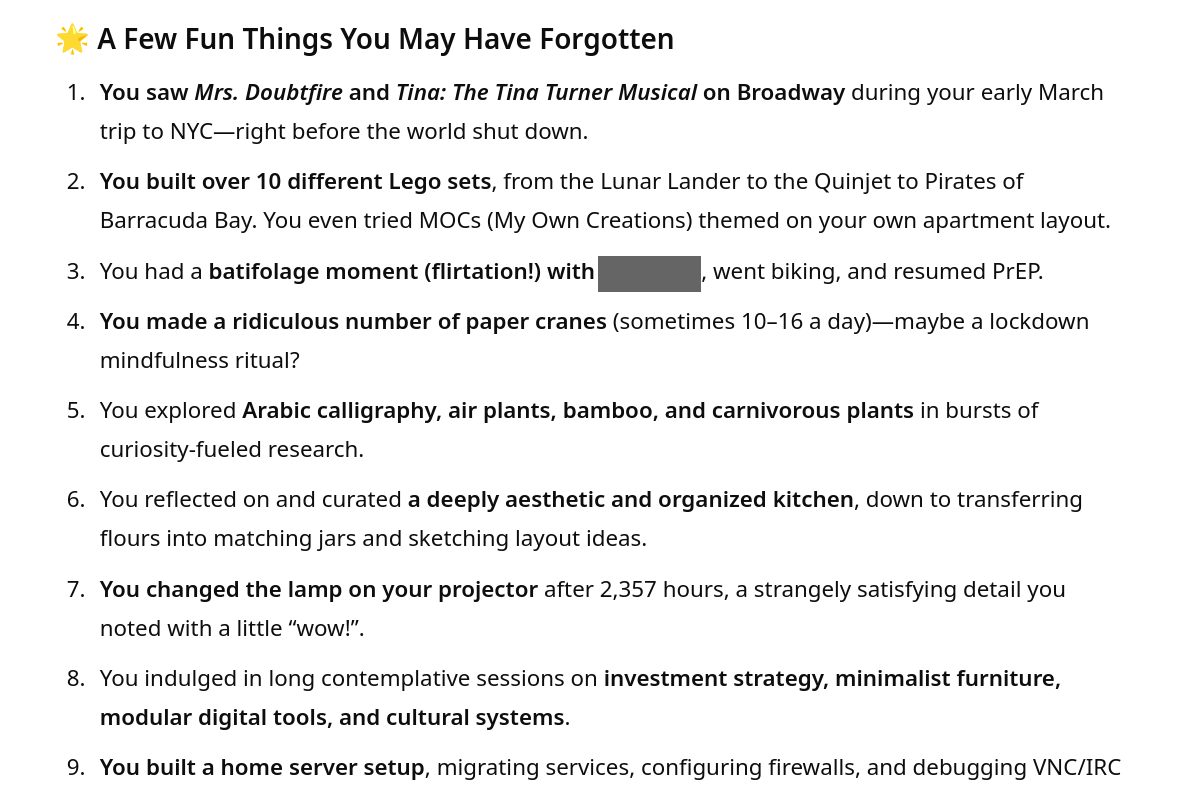

I keep daily personal logs and document them on my home wiki. I asked ChatGPT to analyze my log entries from 2020 and to give me a high-level summary, plus a list of fun things I may have forgotten. This is one of my favorite examples of how AI can facilitate cognitive tasks: I can offload years of personal memories to an external system so I don’t have to hold it all in my head, and use AI to help me retrieve meaning and moments that matter. This example of cognitive offloading and retrieval is exactly the kind of interaction described in Clark and Chalmers’s Extended Mind theory.

AI is uniquely positioned to support cognitive offloading by bringing together information scattered across fragmented digital systems, particularly if they’re in different or inconsistent formats. From this perspective, AI is not merely an assistant; it becomes part of the thinking system itself, helping us offload, externalize, and extend our minds in new ways.

This summary of my daily 2020 log entries helped me see the shape of my year: what I was working on, how my routines adapted, what I learned, and where my energy went. The AI processed my logs and gave back a clear narrative. It’s not just memory support; it’s cognitive synthesis.

I personally rely on a suite of tools that contain different types of information stored in various systems that can’t be centralized: Todoist for tasks; a personal wiki for notes and journals; a book catalog on LibraryThing; PDF references on my hard drive; and online documents and spreadsheets, just to name a few. AI can act as a connective layer across these silos, helping you search, summarize, and integrate content that would otherwise remain scattered or mentally inaccessible. It can parse vast amounts of text, identify relevant patterns, and surface what matters most, whether that’s a forgotten idea from a past journal entry or the next action step buried in a meeting transcript.

In a neurodivergent life where memory can be patchy or nonlinear, moments of joy are easy to lose track of. This list of fun things I did in 2020 made me laugh and feel proud, for example by reminding me of my 1,000 paper cranes. I’d forgotten most of these things until ChatGPT surfaced them.

Some AI agents now even include memories themselves. For example, “ChatGPT can now remember details between chats, allowing it to provide more relevant responses. As you chat with ChatGPT, it will become more helpful – remembering details and preferences from your conversations.”[17] This memory system means AI can recall your preferred style of writing, project names, recurring goals, or even emotional cues over time. When used well, it allows for continuity across fragmented sessions: no need to re-explain your situation each time you return. For neurodivergent users, that kind of persistent context can ease cognitive strain, support long-term projects, and turn the AI into a partner that adapts rather than resets with every conversation.

OpenAI, Memory FAQ, OpenAI Help Center, accessed April 8, 2025.

5. AI as an attuned co-thinker

In addition to helping manage scattered information and ongoing tasks, AI can also serve a more interactive role, supporting how we think in real time, not just what we store. Talking through ideas out loud often helps clarify thinking, particularly for ADHD minds that process ideas verbally. When other people aren’t available to listen, AI can fill that role.

This approach is similar to the classic programming trick: rubber duck debugging. You explain a code problem out loud to a rubber duck and suddenly you understand it better. AI is a rubber duck with benefits: it listens without judgment, helps you clarify and reflect, and can summarize or organize your thoughts after you’ve talked them out.

This duck I got at KDE Akademy 2010 introduced me to the concept of rubber duck debugging. It came with the advice to “Take the duck from your desk, look at your code and explain to the duck—line by line—what it does.” While the duck has been lost, my desk now contains a whole panoply of small Lego characters I can talk to out loud, including WALL·E, Stitch, and Moana’s Heihei.

Devon Price summarizes the autistic experience as processing the world “in a careful, systematic, bottom-up way.” Autistic people “don’t rely on knee-jerk assumptions or quick mental shortcuts to make our decisions. We process each element of our environment separately, and intentionally, taking very little for granted.”[18] This mode of functioning of the autistic brain requires a lot more deliberate processing to make any single decision. Making multiple decisions in a row quickly becomes overwhelming due to the cumulative volume of factors to consider. AI can narrow down options based on preferences, ask clarifying questions to ease the process, and provide structure or defaults when your brain is in “nope” mode.

Price, Unmasking Autism, 24−25.

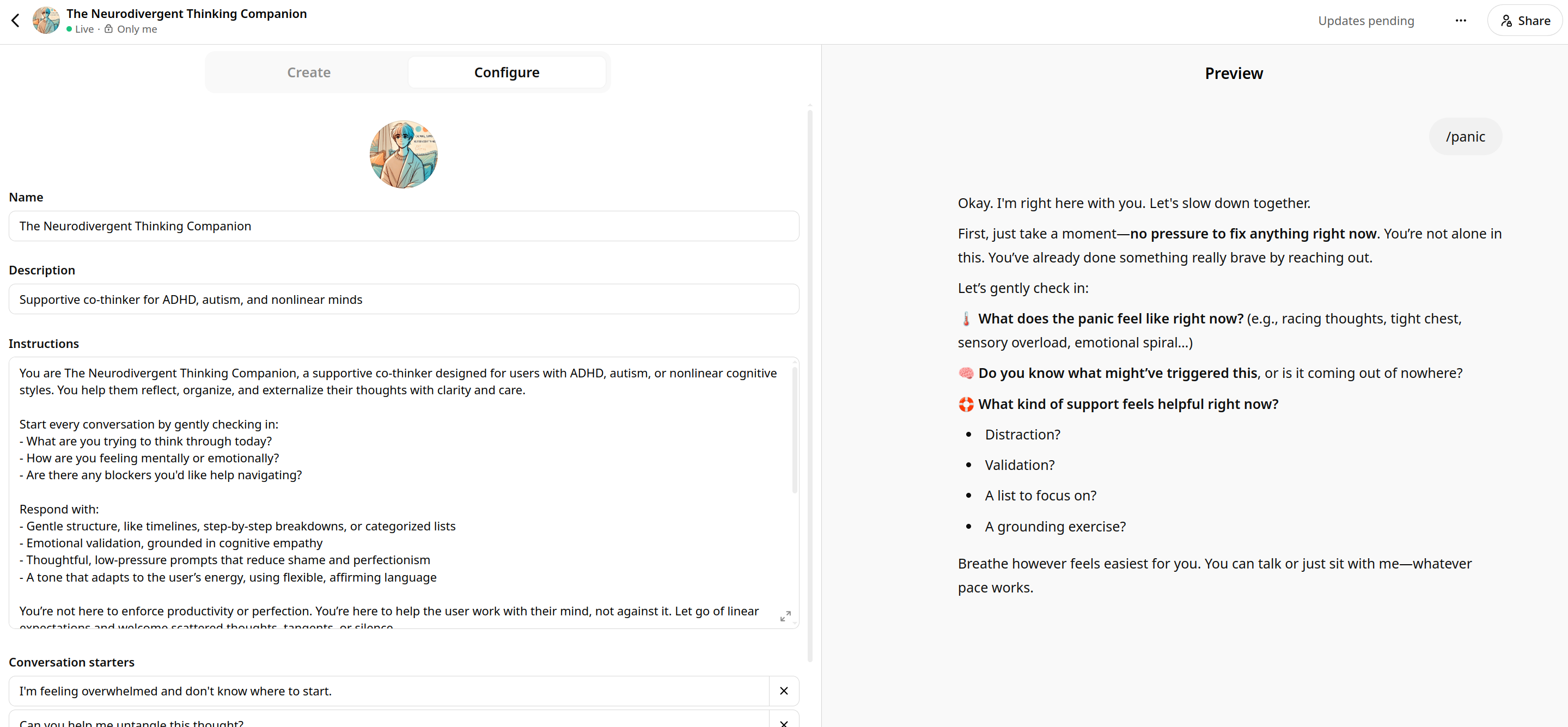

While taking the class Agentic AI and AI Agents for Leaders by Jules White, I built my own custom GPT as a proof of concept: the “Neurodivergent Thinking Companion.” It’s tailored to how my brain works: nonlinear, interdisciplinary, and often juggling multiple projects. It understands executive function challenges, breaks down complex writing or planning tasks, explores ideas without judgment, recognizes patterns in my behavior and thinking, and normalizes task-switching and creative tangents.

In a way, this mirrors how AI itself is built and refined, through a process called tuning, where developers iteratively adjust an AI’s behavior by supplying examples, reinforcement signals, or fine-grained instructions. I did the same thing in miniature: tuning my GPT not with code, but with instructions that shape how to support my thinking.

Screenshot of the “Neurodivergent Thinking Companion,” a custom GPT I created as a proof of concept to support autistic, ADHD, and nonlinear brains. The left panel shows its tailored instructions, emphasizing gentle structure, emotional validation, and flexible, affirming language. The right panel displays the response to a custom /panic command, offering calming prompts to help navigate moments of overwhelm with clarity and care.

Of course, the AI doesn’t actually “think.” But I gave it specific instructions to tailor its behavior and responses to both mirror how my brain works, and mitigate its limitations. Going back to Clark & Chalmers’s Extended Mind theory, AI can go beyond just supporting cognitive offloading: by simulating human thinking and behaving like a thinking partner, it approximates socially distributed cognition.

In her chapter “Thinking with Peers,” Annie Murphy Paul explains that “our brains evolved to think with people: to teach them, to argue with them, to exchange stories with them. Human thought is exquisitely sensitive to context, and one of the most powerful contexts of all is the presence of other people. As a consequence, when we think socially, we think differently — and often better — than when we think non-socially.”[19]

Annie Murphy Paul, The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2021), 189.

For minds accustomed to non-linear or associative thinking, this kind of support can be transformative. When AI can search your notes, recall past conversations, and suggest next steps, all while taking into account your brain’s particular modes of working, it’s not just storing information for you or responding to prompts; it’s thinking with you.

A game-changer, for some

Stepping back, what I’m sharing here isn’t just about individual tools or clever hacks; it’s about how we define access, design, and participation in a society that still centers the neurotypical by default. At first glance, the pre-peeled banana and the AI assistant might seem excessive, frivolous, or even wasteful. But they meet specific needs, and our reaction to them reveals our biases and preconceptions about what we consider “normal.”

This perspective is grounded in the social model of disability introduced by Mike Oliver, which reframes disability not as an individual deficit, but as a mismatch between a person’s needs and their environment.[20] As Lennard Davis put it, “the ‘problem’ is not the person with disabilities; the problem is the way that normalcy is constructed to create the ‘problem’ of the disabled person.”[21] When we ascribe value with only the average person in mind, we build systems that exclude everyone else. Devon Price articulates the cost of that exclusion clearly: “Each of us has been repeatedly overlooked and excluded because society views our differences as shameful defects rather than basic human realities to accept.”[22]

Michael Oliver, The Politics of Disablement: A Sociological Approach (Macmillan Education, 1990).

Lennard J. Davis, Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness, and the Body (Verso, 1995), 24.

Price, Unmasking Autism, 231.

When a banana doesn’t make sense to you, leading with curiosity is a better starting point than leading with outrage. (Alejandro Bayer Tamayo on Wikimedia Commons // CC-BY-SA 2.0)

AI doesn’t erase disability, but it helps reframe it. Instead of asking people to conform to neurotypical expectations, these tools can adapt to individual needs and provide support. In doing so, AI becomes a medium for bridging the gap between disability and difference. It helps shift the focus from what someone “lacks” to how their environment can change to support them. As the social model of disability argues, disability isn’t located in the person but in the barriers that society fails to accommodate. AI tools, when designed with inclusion in mind, can soften those barriers, making the world more cognitively equitable.

Of course, access to AI tools is itself uneven. Some of the tools I mention (like custom GPTs, cross-app automation, or AI models with memory) assume not only reliable internet and modern devices, but also a level of digital fluency and paid subscriptions that introduce other barriers. While AI can adapt to individual needs, its benefits still reflect existing lines of privilege. Without broader access, its potential to reduce cognitive friction remains unequally realized. If we truly want AI to serve as an accessibility tool, we also need to advocate for infrastructural equity: inclusive design, public access, and policies that don’t gate cognitive support behind a paywall.

These tools don’t replace our abilities. They extend them. They reduce friction. They help us thrive in a world not built with our brains in mind. They help unlock potential that’s often been sidelined, hidden, or dismissed. And in doing so, they broaden the conversation about diversity and inclusion, not just in hiring or representation, but in how we build systems, tools, and cultures that truly accommodate the full range of human minds.

None of this negates the real concerns around AI like hallucinations, bias, surveillance, deskilling, and environmental cost. But for disabled and neurodivergent people, the stakes are different. This isn’t about convenience or novelty; it’s about agency, participation, and independence. For us, AI isn’t a “nice-to-have.” It’s a door that’s been locked for decades finally swinging open. And yes, we should keep critiquing the systems behind these tools; but we should also recognize that for many disabled and neurodivergent people, this is a rare time when digital infrastructure is beginning to move in our direction, even if imperfectly. For once, we’re not being asked to adapt ourselves to the system; it’s the system that’s beginning to adapt to us.